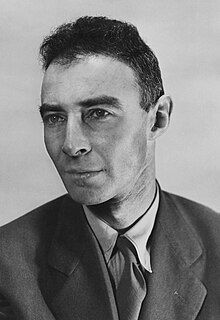

J. Robert Oppenheimer

|

BiographyJ. Robert Oppenheimer (born Julius Robert Oppenheimer; /ˈɒpənhaɪmər/ OP-ən-hy-mər; April 22, 1904 – February 18, 1967) was an American theoretical physicist who served as the director of the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II. He is often called the "father of the atomic bomb" for his role in overseeing the development of the first nuclear weapons. Born in New York City, Oppenheimer obtained a degree in chemistry from Harvard University in 1925 and a doctorate in physics from the University of Göttingen in Germany in 1927, studying under Max Born. After research at other institutions, he joined the physics faculty at the University of California, Berkeley, where he was made a full professor in 1936. Oppenheimer made significant contributions to physics in the fields of quantum mechanics and nuclear physics, including the Born–Oppenheimer approximation for molecular wave functions; work on the theory of positrons, quantum electrodynamics, and quantum field theory; and the Oppenheimer–Phillips process in nuclear fusion. With his students, he also made major contributions to astrophysics, including the theory of cosmic ray showers, and the theory of neutron stars and black holes. In 1942, Oppenheimer was recruited to work on the Manhattan Project, and in 1943 was appointed director of the project's Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, tasked with developing the first nuclear weapons. His leadership and scientific expertise were instrumental in the project's success. On July 16, 1945, he was present at the first test of the atomic bomb, Trinity. In August 1945, the weapons were used against Japan in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to date the only use of nuclear weapons in an armed conflict. In 1947, Oppenheimer was appointed director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and chairman of the General Advisory Committee of the new United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He lobbied for international control of nuclear power to avert nuclear proliferation and a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union, and opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb, partly on ethical grounds. During the second Red Scare, these stances, together with his past associations with the Communist Party USA, led to an AEC security hearing in 1954 and the revocation of his security clearance. He continued to lecture, write, and work in physics, and in 1963 was given the Enrico Fermi Award as a gesture of political rehabilitation. In 2022, the U.S. federal government vacated the 1954 revocation of his security clearance. In 1942, Oppenheimer was recruited to work on the Manhattan Project, and in 1943 was appointed director of the project's Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico, tasked with developing the first nuclear weapons. His leadership and scientific expertise were instrumental in the project's success. On July 16, 1945, he was present at the first test of the atomic bomb, Trinity. In August 1945, the weapons were used against Japan in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to date the only use of nuclear weapons in an armed conflict. In 1947, Oppenheimer was appointed director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and chairman of the General Advisory Committee of the new United States Atomic Energy Commission (AEC). He lobbied for international control of nuclear power to avert nuclear proliferation and a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union, and opposed the development of the hydrogen bomb, partly on ethical grounds. During the second Red Scare, these stances, together with his past associations with the Communist Party USA, led to an AEC security hearing in 1954 and the revocation of his security clearance. He continued to lecture, write, and work in physics, and in 1963 was given the Enrico Fermi Award as a gesture of political rehabilitation. In 2022, the U.S. federal government vacated the 1954 revocation of his security clearance. |

Early career

Teaching

Oppenheimer was awarded a United States National Research Council fellowship to the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in September 1927. Bridgman also wanted him at Harvard, so a compromise was reached whereby he split his fellowship for the 1927–28 academic year between Harvard in 1927 and Caltech in 1928.[33] At Caltech, he struck up a close friendship with Linus Pauling; they planned to mount a joint attack on the nature of the chemical bond, a field in which Pauling was a pioneer, with Oppenheimer supplying the mathematics and Pauling interpreting the results. The collaboration, and their friendship, ended after Oppenheimer invited Pauling's wife, Ava Helen Pauling, to join him on a tryst in Mexico.[34] Oppenheimer later invited Pauling to be head of the Chemistry Division of the Manhattan Project, but Pauling refused, saying he was a pacifist.

In the autumn of 1928, Oppenheimer visited Paul Ehrenfest's institute at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, where he impressed by giving lectures in Dutch, despite having little experience with the language. There, he was given the nickname of Opje, later anglicized by his students as "Oppie". From Leiden, he continued on to the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich to work with Wolfgang Pauli on quantum mechanics and the continuous spectrum. Oppenheimer respected and liked Pauli and may have emulated his personal style as well as his critical approach to problems.

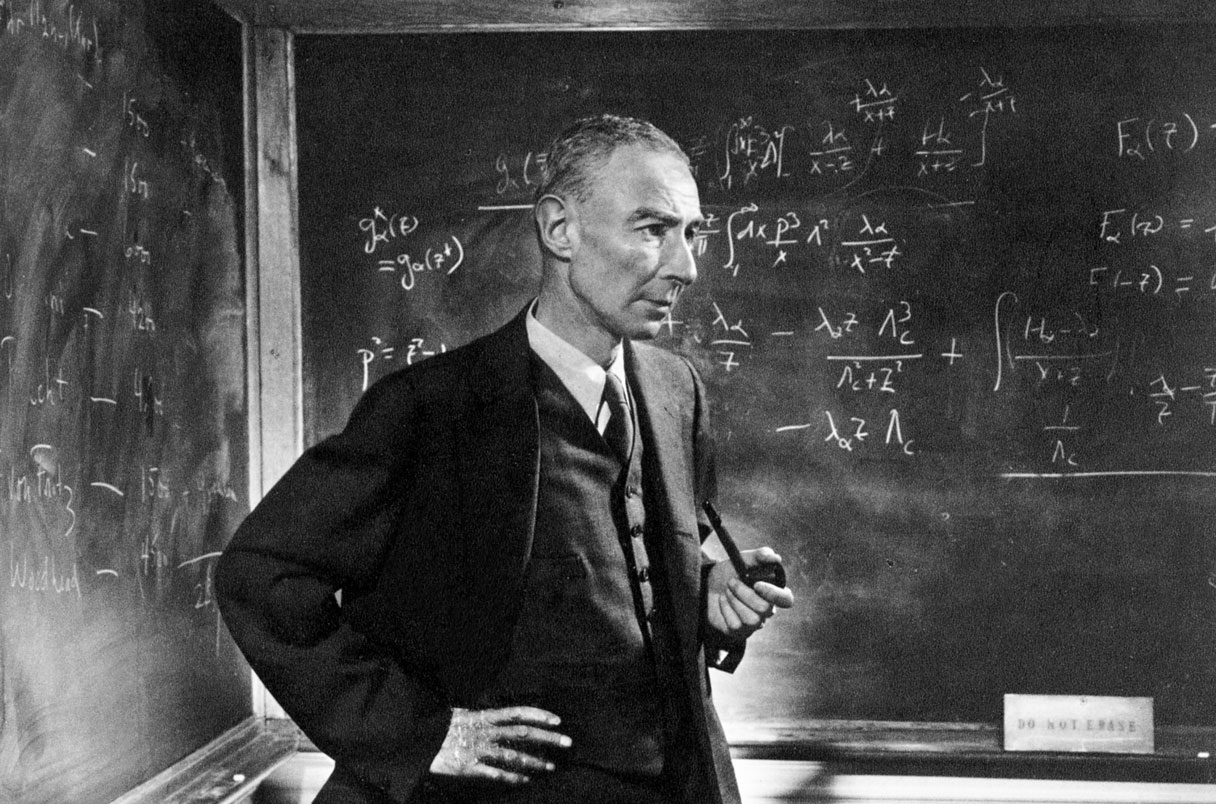

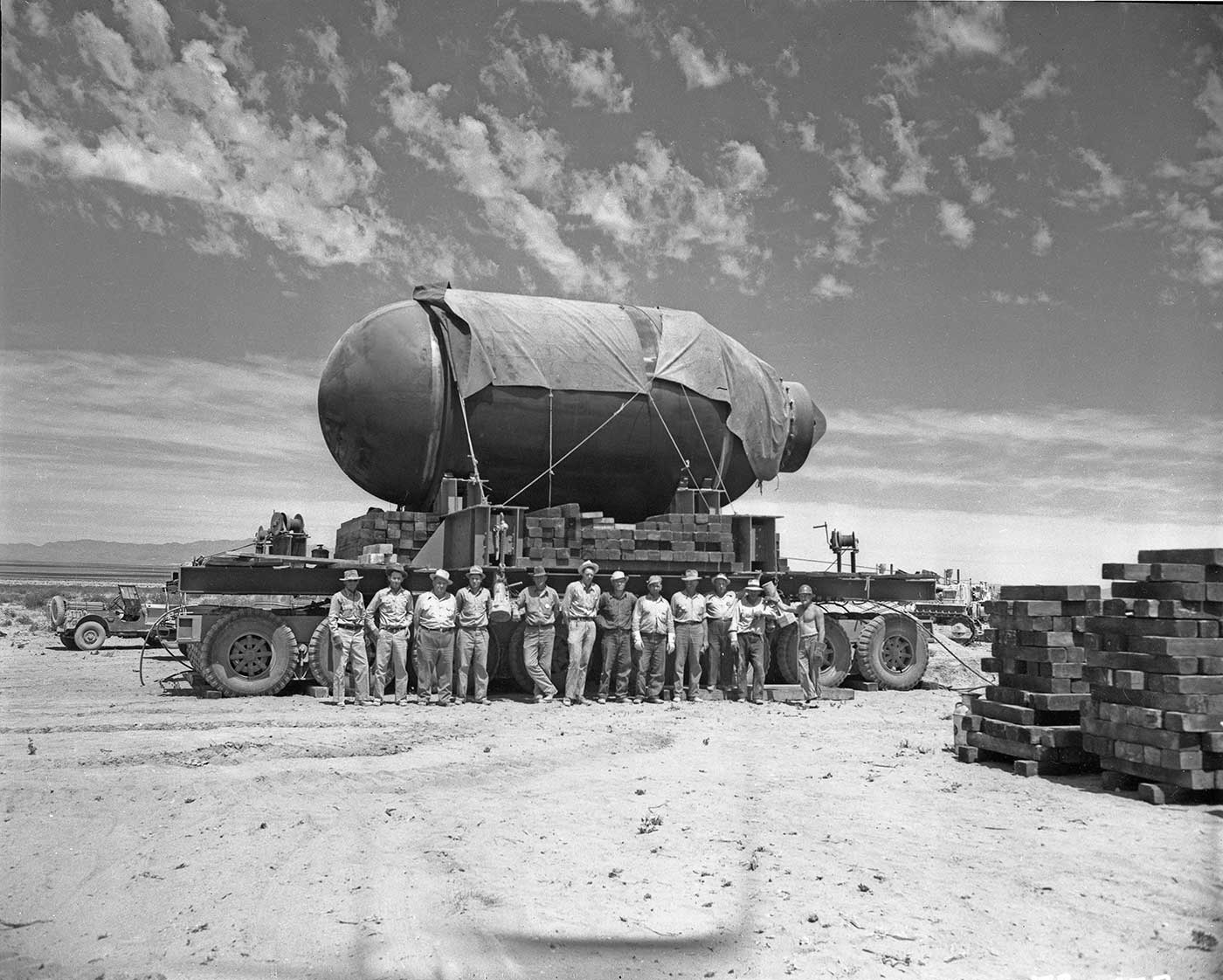

University of California Radiation Laboratory staff (including Robert R. Wilson and Nobel prize winners Ernest Lawrence, Edwin McMillan, and Luis Alvarez) on the magnet yoke for the 60-inch (152 cm) cyclotron, 1938. Oppenheimer is the tall figure holding a pipe in the top row, just right of center.

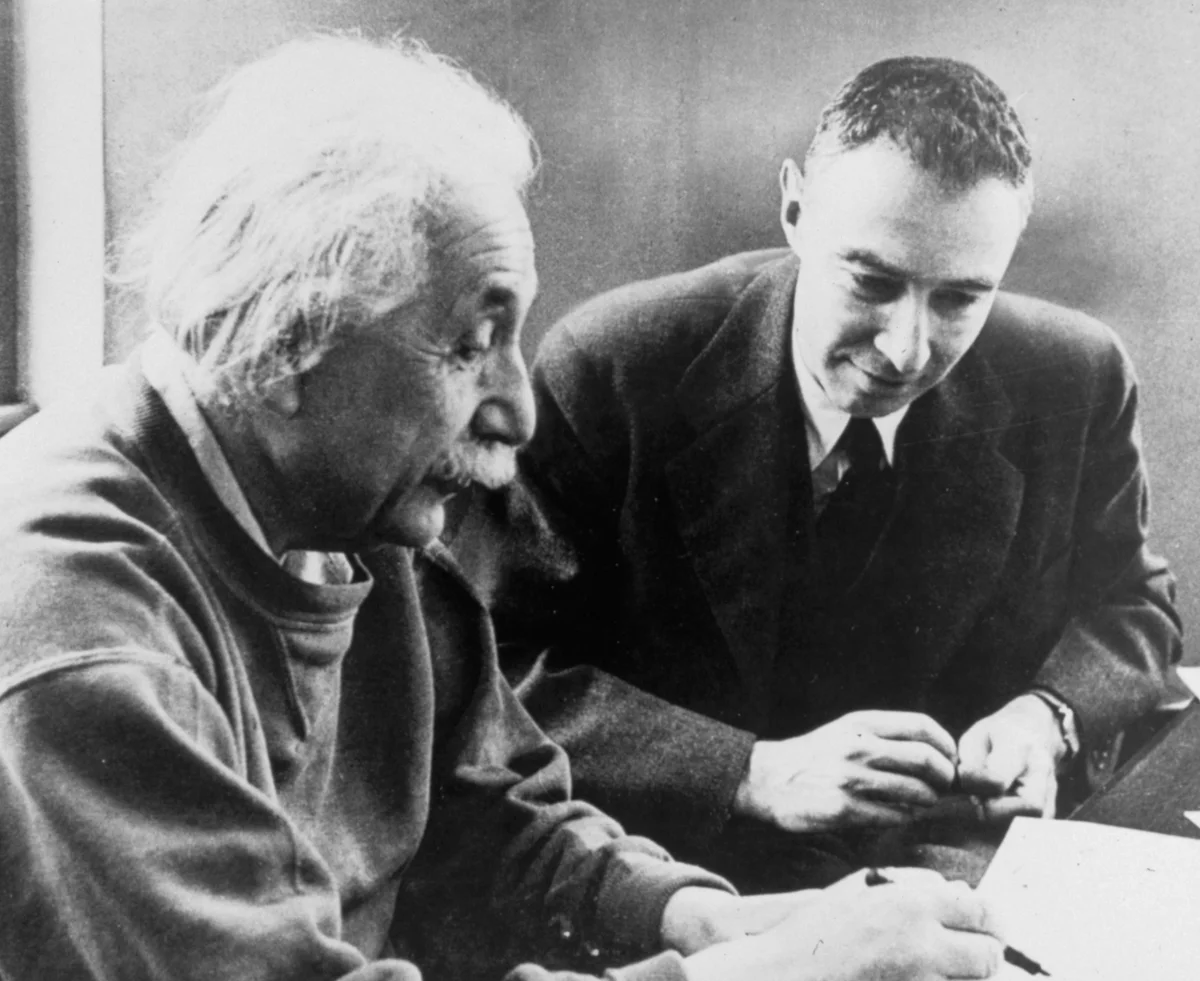

After World War II, J. Robert Oppenheimer became director of the Institute for Advanced Study..

Scientific work

Oppenheimer did important research in theoretical astronomy (especially as related to general relativity and nuclear theory), nuclear physics, spectroscopy, and quantum field theory, including its extension into quantum electrodynamics. The formal mathematics of relativistic quantum mechanics also attracted his attention, although he doubted its validity. His work predicted many later finds, including the neutron, meson and neutron star.

Initially, his major interest was the theory of the continuous spectrum. His first published paper, in 1926, concerned the quantum theory of molecular band spectra. He developed a method to carry out calculations of its transition probabilities. He calculated the photoelectric effect for hydrogen and X-rays, obtaining the absorption coefficient at the K-edge. His calculations accorded with observations of the X-ray absorption of the Sun, but not helium. Years later, it was realized that the Sun was largely composed of hydrogen and that his calculations were correc.

Projects

Manhattan Project

On October 9, 1941, two months before the United States entered World War II, President Franklin D. Roosevelt approved a crash program to develop an atomic bomb. Ernest Lawrence brought Oppenheimer into the Manhattan Project on October 21. Oppenheimer was assigned to take over the project's specific bomb-design research by Arthur Compton at the Metallurgical Laboratory. On May 18, 1942, National Defense Research Committee Chairman James B. Conant, who had been one of Oppenheimer's lecturers at Harvard, asked Oppenheimer to take over work on fast neutron calculations, a task Oppenheimer threw himself into with full vigor. He was given the title "Coordinator of Rapid Rupture"; "rapid rupture" is a technical term that refers to the propagation of a fast neutron chain reaction in an atomic bomb. One of his first acts was to host a summer school for atomic bomb theory in Berkeley. The mix of European physicists and his own students—a group including Serber, Emil Konopinski, Felix Bloch, Hans Bethe, and Edward Teller—kept themselves busy by calculating what needed to be done, and in what order, to make the bomb

Trinity

In the early morning hours of July 16, 1945, near Alamogordo, New Mexico, the work at Los Alamos culminated in the test of the world's first nuclear weapon. Oppenheimer had code-named the site "Trinity" in mid-1944, saying later that the name came from John Donne's Holy Sonnets; he had been introduced to Donne's work in the 1930s by Jean Tatlock, who killed herself in January 1944.

Rabi described seeing Oppenheimer somewhat later: "I'll never forget his walk ... like High Noon ... this kind of strut. He had done it."[162] Despite many scientists' opposition to using the bomb on Japan, Compton, Fermi, and Oppenheimer believed that a test explosion would not convince Japan to surrender.[163] At an August 6 assembly at Los Alamos, the evening of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Oppenheimer took to the stage and clasped his hands together "like a prize-winning boxer" while the crowd cheered. He expressed regret that the weapon was ready too late for use against Nazi Germany.

Gallery

"Now, I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds." - J. Robert Oppenheimer